The Ultimate Guide to Epicurus

Biography, ideas, books

Contents:

Who was Epicurus?

Epicurus (341-270 BC) is often seen as an advocate of a luxurious life, rich in good food and other pleasures. This is incorrect. Epicurus was, if anything, an ascetic: someone who thought that pleasures and good food have a negative effect on our happiness and that we should train ourselves to enjoy the simpler pleasures of life.

Epicurus was born around 341 BCE, seven years after Plato’s death. He grew up in the Athenian colony of Samos, an island in the Mediterranean Sea, close to what is today the shore of Turkey.

Epicurus was about 19 when Aristotle died and he studied philosophy under followers of Plato and Democritus. Democritus had developed a theory of atoms, tiny, indivisible particles of matter, and Epicurus saw in this a way out of superstitious beliefs in Gods, spirits and fate.

Read more about the life of Epicurus in our short biography right here:

Epicureanism: The main idea

Epicureanism is not about boundless enjoyment. Instead, Epicurus advocates that we should study our desires and learn to distinguish those that are natural from those that are artificial and unnecessary. By limiting our desires to the natural and necessary ones, we can achieve lasting happiness.

At the basis of Epicureanism lies a trick. Instead of expecting something and then randomly having the universe destroy one’s expectations, you should, Epicurus says, lower your expectations so that most of what can happen will be better than what you expect.

We go into more detail in this article:

Epicurus: The wise man and the fool

“The misfortune of the wise is better than the prosperity of the fool,” Epicurus writes in his letter to Menoeceus.

On first sight, this is a strange statement. Why should misfortune ever be better than prosperity? Is Epicurus cheating himself here, a philosopher, unsuccessful in life, trying to comfort himself for his failures? Or is there more behind this statement? And what exactly?

For Epicurus, being wise means to be in control one’s desires and to lead a rational, measured life. In such a life, misfortune has little meaning, because the happiness of a wise person does not depend on luck or good fortune. Even catastrophic events cannot affect one who does not depend on material goods for one’s happiness.

On the other hand, a prosperous fool is still a fool: they will always want more, and they will always be unhappy about their present situation.

This article goes into more depth about this fascinating look at how we can achieve lasting happiness in life:

Epicurus on desires

Epicurus distinguishes three kinds of desires:

-

The natural and necessary desires. These are desires that will cause pain if not fulfilled: the desire for food, water, and a safe place to sleep;

-

The natural but unnecessary desires. These are desires that don’t cause pain if not fulfilled, but they are still natural in the sense that we have them due to our nature, and that they can be fulfilled by what nature freely provides: the desire for friendship, for a partner perhaps (Epicurus is not very clear about what exactly falls into this category); and

-

The unnatural and vain desires. These are desires for money, for jewels, for a sports car, for a high place in society. They don’t cause any pain if not fulfilled – quite the opposite. Fulfilling them causes pain and annoyances, like having to work more than necessary, not having time for friends and family, having to save money over long periods of time and so on.

Read more about Epicurus’ theory of desires in this article:

Epikur glaubte, dass der zuverlässigste Weg, glücklich zu sein, darin besteht, seine Wünsche zu reduzieren, bis es einfach ist, sie zu befriedigen.

Reading Epicurus: Pleasure and pain

For Epicurus, pleasure is nothing but the absence of pain. Pain can further be subdivided into pain of the body and trouble in the soul. This negative description of happiness is surprising at first sight, but is a necessary component of the Epicurean philosophy of happiness.

Note that here Epicurus does not refer only to bodily pain, like a tooth-ache or such. “Pain” for him is every sensation that is negative, and that distracts us from being at peace. This can be a toothache, but it can also be psychological states like anxiety.

In this article, we examine Epicurus’ ideas about pleasure and pain in more detail:

Epicurus also distinguishes “static” from “moving” pleasures. While I am eating something, I have the fleeting, moving pleasure of tasting the food. But after that is gone, I still have the much more constant pleasure of not being hungry any more. This is a static pleasure, and these static pleasures are, for Epicurus, the best and most dependable source of happiness.

Read more about Epicurus’ theory of pleasures here:

Epicurus on old age and death

The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus emphasises that, in a world that works according to physical laws, nobody ought to be afraid of either the gods or one’s own death – for when death arrives, we will be gone. But is this a convincing argument?

In an atomistic universe, like Epicurus sees the world, death would be nothing but the dissolution of the body into its constituent atoms that would go on to form new things. Consciousness would cease with death and so neither would we be able to perceive our own death, nor would there be any afterlife to experience.

In this way, Epicurus tries to remove the fear of death, which, he says, is one of the greatest obstacles to human happiness.

A beautiful book that discusses old age from an Epicurean perspective is Daniel Klein’s Travels with Epicurus. Read more about what Epicurus calls “the trouble in the soul” and about Daniel Klein’s book right here:

Epicurus on friendship

Much has been said about Epicurus and the value of friendship in his philosophy. According to some commentators, Epicurus was so associated with the concept of friendship in the ancient world, that when the Christians came around, they avoided talking about friendship, so as to not be confused with the Epicureans.

In the Principal Doctrines, Epicurus says:

Of all the means which are procured by wisdom to ensure happiness throughout the whole of life, by far the most important is the acquisition of friends.

And in the Vatican Sayings, he adds:

Every friendship in itself is to be desired; but the initial cause of friendship is from its advantages. … We do not so much need the assistance of our friends as we do the confidence of their assistance in need.

But what exactly does he mean by that? Read more about Epicurus’ views on friendship in this article:

Stephanie Mills: Epicurean Simplicity

In her book “Epicurean Simplicity,” author and activist Stephanie Mills analyses what is wrong with our modern way of life – and she goes back to the philosophy of Epicurus to find a cure. Mills’ book is as beautiful and relaxing as it is inspiring – a passionate plea for a life well-lived, a life that is less wasteful and more meaningful.

Read a short review of Mills’ book right here on Daily Philosophy:

Epicurus and Luddism

Stephanie Mills’ book brings us to the question of Epicurus’ Luddism.

Luddism as a social and political movement begins with the introduction of mechanised looms and other machinery during the British industrial revolution. Luddism, at its core, is the thesis that technology must serve human life, rather than the other way round, and that often the use of technologies does not make for better or happier societies.

Read more about the history and main theses of Luddism here:

Epicurus does not take any clear stance on technology. But his system suggests that reducing one’s desires is preferable to fulfilling them because then one can achieve happiness without eternally chasing material goods. Technology, at least in the way that it is deployed in capitalism (based on planned obsolescence) contradicts the essential simplicity of the ideal Epicurean life. Epicurus would likely have sympathised with Luddism.

Read more about Epicurus’ possible stance towards technology here:

For a different take on technology, have a look at Erich Fromm’s ideas about why technology in our societies is not necessarily good for our happiness:

If you are interested in Fromm more generally, we also have an Ultimate Guide to the Philosophy of Erich Fromm on Daily Philosophy:

How Much Money do We Need?

Epicureans would not only make the point that we don’t need an excessive amount of technology in order to be happy, but also what we don’t need nearly as many material goods as we think we need. From Diogenes and Epicurus to Erich Fromm and modern minimalism activists, from ancient times to the present, there is a long tradition of philosophers suggesting that long-lasting happiness might be easier to achieve if we don’t primarily focus on material gains.

Read more about whether money can make us happy here:

Hermits go to the extreme of departing from the world and living a life almost entirely devoid of material goods. But are they happy? Have a look at this article, where we discuss just this question:

How to Live Epicurus Today

After we have talked so much about the theory of Epicurus, of course we are interested in the question whether one can, in principle, strive to live an Epicurean life in today’s world.

Epicurus thought that the easiest way to lead a happy life was to focus on one’s natural needs — and the natural ways of satisfying them.

“Whatever is natural,” he writes, “is easily procured and only the vain and worthless hard to win.” (Letter to Menoeceus)

One can imagine that to be true in ancient Athens, a warm, fertile place, a small town by today’s standards, surrounded by orchards, olive groves and a fish-filled sea. But is it true today?

The Queen of England eats her own organic berries from the grounds of Windsor Castle (or wherever they grow them) — but many studies have found that “low-income neighborhoods offer greater access to food sources that promote unhealthy eating.” In our societies, so-called “fast food” is easier to procure, to use Epicurus’ words, than proper, natural food.

So where does this leave us? Has Epicurean living become so expensive today as to exclude most of us from practising it? Does one need to be rich in order to be able to afford the simple life?

Read more about this question (and a bit about the Queen of England) here:

Study Guide to the Principal Doctrines

If you’d like to go deeper into Epicurus, or just to read a very short and easy to understand ancient philosophy classic, Epicurus Principal Doctrines are just the thing. The text is very accessible, consisting only of 40 short, numbered paragraphs that contain all of Epicurus’ philosophy of happiness.

Here I have put together a study guide that presents and explains the original text of the Principal Doctrines. It can be used for a class on Epicurus’ philosophy of happiness or it can form the basis for a reading group or book club meeting.

If you’d like to read Epicurus’ Principal Doctrines with in an understandable version and with the help of many explanations and clarifying comments, have a look at our Principal Doctrines Introduction and Study Guide:

Epicurus’ Major Works

Epicurus wrote many works (Diogenes Laertius, from whom we know most about Epicurus, lists 44 books, most lost today). But his theory of happiness is contained primarily in three short pieces:

- The Principal Doctrines is a collection of 40 sayings that summarise the whole of the Epicurean philosophy of life.

- The Letter to Menoeceus, who was one of Epicurus’ students, is one of three Epicurean letters that we have. It is a less systematic and slightly more superficial text than the Principal Doctrines, but covers essentially the same ground.

- Finally, the so-called Vatican Sayings are a collection of 81 quotes that were discovered in the Vatican Library in 1888. Some of them are almost identical to some of the Principal Doctrines, but others cover also different topics.

Both the Principal Doctrines and the Letter to Menoeceus we know of only because the 3rd century AD author Diogenes Laertius quoted them in full in his work “Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers,” which also contains source material from many other Greek philosophers.

Thankfully, all these sources are available in English and anyone can read them for free on the Internet. Here are the links:

- Principal Doctrines, tr. Hicks

- Letter to Menoeceus, tr. Hicks

- Diogenes Laertius, Chapter on Epicurus. This one includes the Greek text (click on “Load” top right to see the Greek).

For a more modern translation, you can have a look at Erik Anderson’s 2006 translation. It is very readable and explains many points that are more cryptic in Hicks’ older translation.

Daily Philosophy’s top picks

There’s little need to buy the books of Epicurus, since they’re all available online, both in the original Greek and in various translations. But if you’d really like a bound book, or you are interested in other works that we discussed, here are some good books to have.

The book we discussed in a separate article, Stephanie Mills on Epicurean Simplicity:

Here is Stephanie Mills’ book “Epicurean Simplicity.” It is a tender meditation on what makes life worth living and a declaration of love to nature and to life.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Philosopher Daniel Klein travels to Greece in search of Epicurean wisdom on how to approach old age:

Daniel Klein: Travels with Epicurus.

A wonderfully human meditation on old age. A man travels to a Greek island with a suitcase full of books, in search of a better, more dignified way to age.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

The works of Epicurus. First the Doctrines in translation:

Epicurus: Principal Doctrines. If you'd like to have a go at reading Epicurus, here are the Principal Doctrines in a handy paperback edition.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

And here we have the Doctrines and the Letter to Menoeceus, both in English and in the original Greek for reference.

Epicurus: Principal Doctrines and Letter to Menoeceus (Greek and English). This edition contains the Greek text. If you can read a bit of Greek, you can read that along with the translation.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

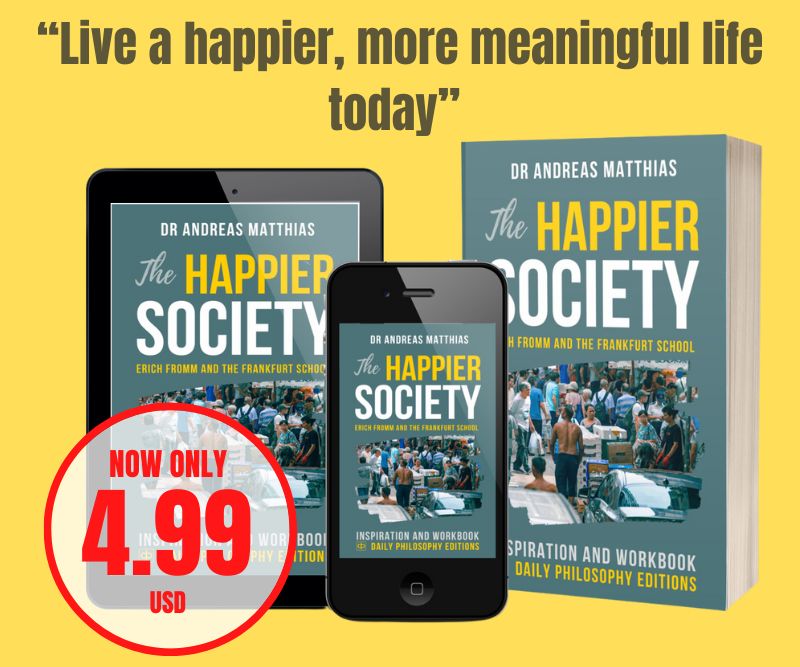

The Happier Society. Erich Fromm and the Frankfurt School.

In this book, philosophy professor, popular author and editor of the Daily Philosophy web magazine, Dr Andreas Matthias takes the reader on a tour, looking at how society influences our happiness. Following Erich Fromm, the Frankfurt School, Aldous Huxley and other thinkers, we go in search of wisdom and guidance on how we can live better, happier and more satisfying lives today.

This is an edited and expanded version of the articles published on tis site.

Get it now! Click here!

◊ ◊ ◊

Title image by NordWood Themes on Unsplash.